The Supreme Court Is Preparing to Overturn a Conversion Therapy Ban That Has Never Been Enforced

The Supreme Court appears poised to dismantle Colorado's conversion therapy ban based on a christian’s hypothetical fear of persecution.

The U.S. Supreme Court appears ready to gut Colorado’s ban on the harmful, discredited practice of anti-LGBTQ+ conversion therapy, even though the state has never punished a single medical professional under the law.

On Tuesday, America’s highest legal authority heard a challenge brought against Colorado’s ban on “pray the gay away” treatments by Kaley Chiles, a Christian therapist who claims that the 2019 law violates her First Amendment right to freedom of speech. Entitled the “Minor Conversion Therapy Law,” the statute prohibits licensed medical professionals from encouraging clients under the age of 18 to “change behaviors or gender expressions or to eliminate or reduce sexual or romantic attraction or feelings toward individuals of the same sex.” The law carves out an exception for religious leaders providing counseling outside the medical profession and does not apply to adults.

While the Colorado law threatens medical providers with a $5,000 fine and potential loss of licensure for violating the ban, Chiles has never faced the risk of either of those outcomes. Colorado has yet to investigate Chiles — or any other medical provider — following the law’s passage. In fact, Colorado’s solicitor general, Shannon Stevenson, affirmed during this week’s oral arguments that Chiles wouldn’t even be liable under the statute: The therapy she provides, as the state noted, doesn’t actually seek to change patients’ attractions, just to offer support. Her work, thus, is not at issue.

“If the therapist told [a patient] or he asked, ‘Can you help me become straight?’” Stevenson clarified of the law, “the answer would be, it would be banned.”

But despite the fact that the named plaintiff in Chiles v. Salazar is not actually affected by the law she is challenging, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority expressed support for her case anyway. If SCOTUS does not outright overturn Colorado’s conversion therapy ban, justices are likely to return the case to a lower court for reconsideration.

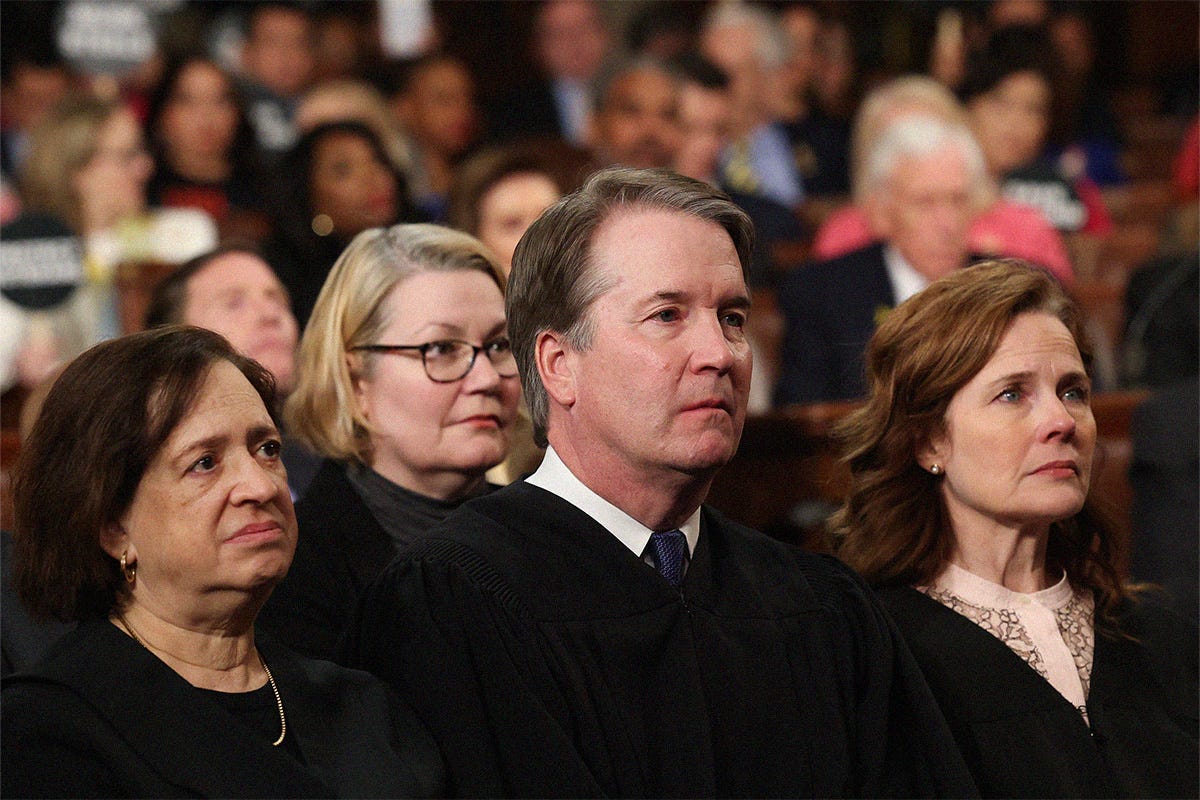

During a swift 90 minutes of oral arguments, the Supreme Court’s right wing continually questioned whether conversion therapy — an ineffective, widely debunked practice that has been condemned by virtually every leading U.S. medical association — is even all that dangerous. Justice Samuel Alito, one of the more conservative members of the bench, questioned whether, in the past, there have been times “when medical consensus has been taken over by ideology.”

“Was there a time when many medical professionals thought that certain people should not be permitted to procreate because they had low I.Q.s?” he asked. “Was there a time when there were many medical professionals who thought that every child born with Down syndrome should be immediately put in an institution?”

And despite the fact that there is overwhelming consensus regarding the fact that conversion therapy results in dramatically increased rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation among survivors of the practice, fellow right-wing Justice Amy Coney Barrett falsely asserted there are “competing strands” of medical opinion on the topic. “Let’s say that you have some medical experts that think gender-affirming care is dangerous to children, and some that say that this kind of conversion talk therapy is dangerous,” she posited. “Can a state pick a side?”

Under questioning from Barrett, the state of Colorado reaffirmed what the data actually shows: Conversion therapy, a loosely defined set of practices ranging from the talk therapy that Chiles offers to shock treatment and water torture, is destructive and even deadly. A 2019 report from The Trevor Project, the nation’s leading LGBTQ+ suicide prevention group, found that 42% of conversion therapy survivors had contemplated taking their own lives within the past 12 months.

“The harms from conversion therapy come from when you tell a young person you can change this innate thing about yourself, and they try and they try and they fail, and then they have shame and they’re miserable, and then it ruins their relationships with their family,” Stevenson said.

While dismissing the expertise of groups like the American Psychological Association and American Medical Association, both of which staunchly oppose conversion therapy, attorneys for Chiles held that she was being censored by a law that doesn’t actually affect her. Jim Campbell of the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), a far-right, anti-LGBTQ+ legal outfit that has previously defended bans on consensual same-sex intimacy, claimed that Colorado’s law forces therapists to become “mouthpieces for the government” by prohibiting them from expressing support for “state disfavored goals.”

“Ms. Chiles is being silenced,” he stated. “The kids and families who want help — this kind of help that she offers — are being left without any support.”

Even though the state of Colorado confirmed that it has no plans to take action against Chiles, the ADF attorney argued that his client had been engaging in self-censorship in fear of future scrutiny. Campbell also claimed that, due to the notoriety of being a Supreme Court plaintiff, complaints targeting her had been brought in recent weeks. (These alleged complaints were not referenced in court documents, nor was evidence of them submitted during Wednesday’s proceedings.) He asserted that there remains a “credible threat of enforcement” against Chiles.

Both conservative and liberal Supreme Court justices signaled sympathy with Campbell’s argument, suggesting there may be bipartisan opposition to the Colorado conversion therapy ban. Alito referred to the law as “viewpoint discrimination,” claiming that it would be permissible for therapists to express support for a patient’s LGBTQ+ identity but not opposition to it. Justice Elena Kagan, a liberal appointed by former President Barack Obama, seemed to agree.

“Let’s just assume that we’re in normal free-speech land rather than in this kind of doctor land,” she said. “And if a doctor says I know you identify as gay, and I’m going to help you accept that, and another doctor says I know you identify as gay, and I’m going to help you change that, and one of those is permissible and the other is not, that seems like viewpoint discrimination.”

Should the Supreme Court find Colorado’s conversion therapy ban unconstitutional, it would be only the most recent time that justices sided against LGBTQ+ rights based upon a hypothetical fear of persecution. When Christian website designer Lorie Smith appealed to SCOTUS for an exemption to Arizona’s nondiscrimination law, which she said would force her to violate her beliefs by making a webpage for a gay wedding, no same-sex couple had ever reached out to solicit her services. Furthermore, Smith didn’t even make wedding sites at the time that the 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis case was originally brought. In June 2023, the Supreme Court ruled narrowly in the plaintiff’s favor anyway.

Wielding its most conservative bench in 90 years, the Supreme Court is unlikely to let details get in the way of another ruling against LGBTQ+ equality. SCOTUS has been on an anti-LGBTQ+ tear over the past year, ruling in favor of parents who wish to opt their children out of LGBTQ+ affirming curricula and permitting states to restrict gender-affirming medical care for minors.

As the Supreme Court debated Chiles v. Salazar this week, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson bluntly questioned her colleagues’ hypocrisy on the subject of what medical treatments are permissible for minors. In Skrmetti v. United States, Jackson noted that SCOTUS was willing to allow conservative lawmakers to regulate trans youth health care, medical treatments that they alleged were harmful. (This is despite the fact that medications like puberty blockers have consistently been found to be safe and effective in alleviating minors’ gender dysphoria, when supervised by a medical professional.) She wondered why, under that logic, letting states ban conversion therapy isn’t the “functional equivalent” of that ruling.

“The regulations work in basically the same way,” Jackson said. “So it just seems odd to me that we might have a different result here.”

A decision in Chiles v. Salazar is expected in the summer of 2026. Currently, at least 27 states (and Washington, D.C.) restrict at least some forms of conversion therapy from being performed on minors, including California, Minnesota, Nevada, New York, and Pennsylvania. Outside the U.S., the practice has been banned in 25 countries and likened to torture by United Nations human rights experts.